Peloton's Race to the Bottom

Is this the company's final lap?

“If you’ve been wondering whether or not Peloton can make an epic comeback, this quarter’s results show the changes we’re making are working.”

Those were the words of Peloton CEO Barry McCarthy, 12 months after he took on the mammoth task of revitalizing the struggling company. However, February’s Q2 earnings report didn’t exactly scream improved performance; losses were $335.4 million compared to $439.4 million the previous year, the company posted $792.7 million in revenues, which did beat projections, and Peloton’s cash flow had improved 83 percent from negative $546.7 million to negative $94.4 million.

It was still bad, just not as bad as it could be. But for much-needed perspective, it was also Peloton’s eighth consecutive quarter without turning a profit.

And now, only a few months after the talk of comebacks, disaster has struck. The company announced a voluntary recall for 2.2 million original Peloton model bikes after it received 35 reports of the seat post breaking and detaching from the bike during use and 13 reports of injuries. This is not Peloton’s first recall-rodeo. Much like the last time, it will be less about the monetary damage and more about the reputational damage it does to a company already on life support.

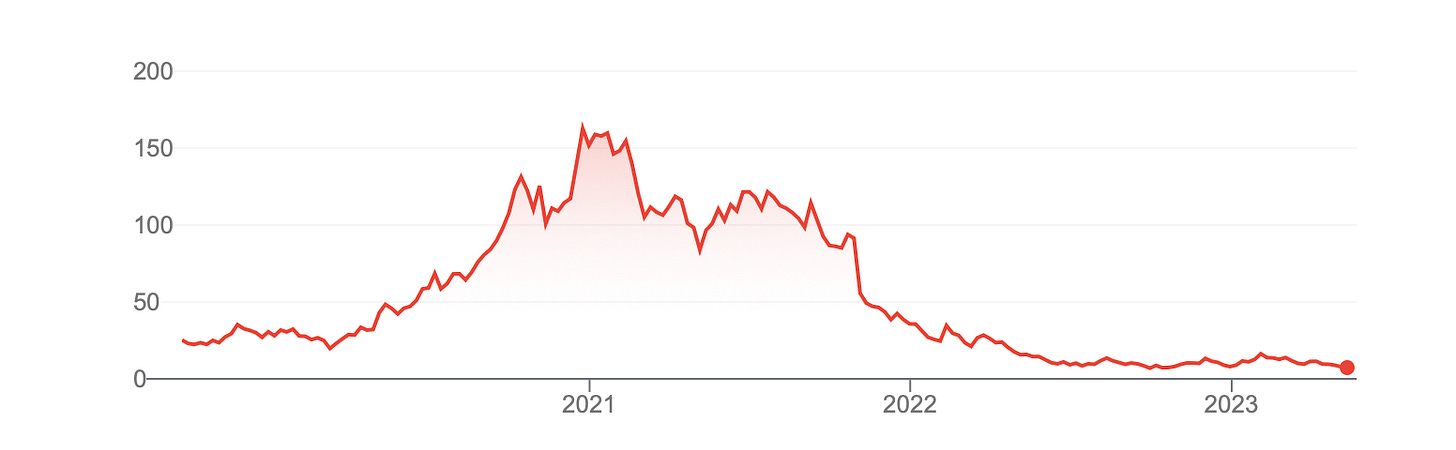

And that came swiftly; the stock dropped nearly 10% on the news, leaving the price at an all-time low of $6.80 — a 95% drop from its all-time high of $167.42.

Rather than a comeback, it’s a callback. And it’s just another in a long line of bad decisions, bad luck and bad performance. All of which begs the question; is this the final lap? Or perhaps the question should be, will the company even finish the lap? Peloton has been in survival mode since the end of the pandemic, and it appears nothing will reverse the trajectory.

The pandemic winner

When the population was forced inside due to the lockdowns, those not content with walking around the block on loop turned to home workouts. Peloton hit the jackpot. Sales surged over 250%, and in January 2021, the stock price hit that all-time high of $167.42 a share. It seemed the company had everything; aspirational branding, social appeal, high-quality equipment and the growth to match.

But in September 2021, the wheels came off.

First, the company had to deal with its first major crisis when its treadmill was linked to accidents and a user’s death. The ensuing recall cost Peloton over $165 million — and far more in damage to its reputation.

Next came the acid test; the world began to return to ‘normal,’ and indoor, in-person gyms once again opened their doors. Could Peloton sustain its momentum? It turns out that WOFH (working out from home) was just a stop-gap measure rather than a permanent habit. As a result, the company’s churn rate increased, losses piled up, and subscriber growth forecasts were slashed. Competitors like Planet Fitness — an in-person gym — quickly recaptured most of their pre-covid memberships, pulling members away from Peloton. Other gym chains will have likely done the same. (At the time of writing, Planet Fitness stock is priced at $69.29).

In a page from the WeWork script, news broke that investors and insiders had cashed out to the tune of almost 500 million dollars during Peloton’s boom while Peloton employees watched their stock options crash and burn. Rumors followed that Peloton was working with consulting firm McKinsey & Co. to cut staff, increase prices, and close stores, looking to undo its rapid expansion over the previous two years. According to the documents published by CNBC, most employees discovered the bad news through the media. They took to their internal company Slack groups to vent, with one employee summarizing the mood. “I’m going to start drinking.” One employee told CNBC that “Morale is at an all-time low.” It was another repetitional hit to a company severely low in, well, reputation.

Thanks to the world reopening, Peloton went from being a company plagued with product shortages to a company plagued with too much inventory. The company admitted it had warehouses filled with stock and a lack of bedrooms looking for a large item to gather dust or hang clothes from. The announcement to pull back on production — hardly a sign that things are going well — caused the stock price to drop back to the pre-public offering price of $29.

In December 2021, Peloton’s crisis of the month was that a certain high-profile character in a not-as-high-profile-as-it-was TV show died from cardiac arrest after — you guessed it — riding a Peloton bike. And the world went bananas over it, leaving the company suffering the all-too-real consequences. The company’s stock dropped 11% in the hours after the show aired — at one point, it left stocks down 73% for the year. Not long after, Credit Suisse downgraded the stock, reducing the price target from $112 to $50.

In February 2022, the company changed leadership, with Barry McCarthy becoming the CEO. (It’s recently come to light that he was convinced by a $168 million pay package). In May 2022, the company had its first earnings call under McCarthy, and it was just more bad news. After spending the last few months digging through the company’s dirty laundry, he admitted that he was surprised to discover Peloton was “weaker on everything supply chain” and struggling with cash flow. Despite his best efforts, including shelving plans for a US-based manufacturing plant, cutting staff and slashing prices, nothing has been able to salvage the company. The company is still losing billions of dollars a year, something many turn a blind eye to when the growth metrics point up, but all the metrics point down. With the latest recall saga, the company is surely running out of runway.

Acquisition is the answer

The future for Peloton is uncertain.

The company is pinning its hopes on its app, which can be used via subscription without needing an expensive workout machine. McCarthy once said the aim was to hit 100 million subscribers, but they haven’t even hit 10 million (some figures estimate 6-7 million subscribers). So where will those other 93 million come from?

That would be through acquisition. Though in this case, Peloton would be the acquisition.

The company has high-quality products and a user base of wealthy people — the exact market other premium brands want to target. Moreover, its ever-lowering price is making a buyout less and less risky. For a giant like Apple, Amazon or Nike, it may drop so low that they can’t pass up the opportunity to bring these users and the connected devices into their own ecosystem. A deal with Apple would make a ton of sense; both are luxury brands combing sleek hardware with subscription-based revenues. The Apple Watch, AirPods, Apple Music, Peloton Bike/Treadmill and service ecosystem is a great package and allows Apple to gain our attention for another hour a day. It also fits Tim Cook’s vision that health will be Apple’s “greatest contribution to mankind.” Apple is also filthy rich, and the purchase of Peloton would be a drop in the ocean. Peloton has always been adamant it can survive on its own —in the last earnings call, McCarthy said the company’s goal was to “control its own destiny”— but a big money offer that guarantees its survival may prove too good to resist.

The story of Peloton has been a rollercoaster to date, and it’s likely still got legs left. But, in some ways, the company has already won the race.

It just happens to be the wrong one: the race to the bottom.